Iceland, which bills itself as the land of fire and ice, has also become the land of foreign visitors.

I should know: My wife and I honeymooned on the island nation in July 2010 and returned for a 48-hour visit in January.

We love it there and so, apparently, do many, many others.

And therein lies the problem.

Consider that the Icelandic Tourist Board reported that 502,300 people visited in 2008.

By 2014, that number had climbed to nearly 1 million. Two years later, that number skyrocketed to 1.8 million.

That means in 2016, visitors outnumbered locals by a ratio of about 6 to 1.

The steady stream of tourists — and its consequences — has not gone unnoticed.

In March, The Financial Times quoted Paul Fontaine, news editor of the English-language The Reykjavík Grapevine: “It’s got to the point where even the tourists are complaining about too many tourists.”

There was a perceptible difference in what I observed in Reykavik during our recent visit compared with 2010.

We had walked Laugavegur, which is one of the main streets in the capital, in 2010, but when I was there in January, I was struck by how tourist-y, bordering almost on honky-tonk it had become.

Souvenir shops catering to out-of-towners and hawking sweatshirts, mugs and Nordic-themed seemed to be bountiful.

One chain retailer, cleverly called I Don’t Speak Icelandic, sells “Enjoy Our Nature” condoms with names such as “Volcanic Eruption.”

Iceland’s penis museum, technically known as the Icelandic Phallological Museum, also had a different, um, feel to it. When we visited in 2010, it was located in the small fishing village of Húsavík.

There, it had a rebellious almost cheeky vibe. Now located in downtown of Reykjavik, it felt more like a gimmicky tourist trap instead of being a genuine reflection of someone’s hobby and passion.

Even the Icelandic people who we found to be reserved but friendly in 2010 now had a certain resigned demeanor/brave face that comes from dealing with hordes of tourists.

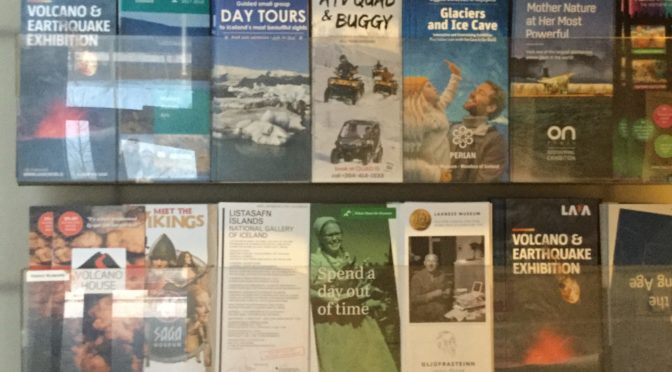

Wherever we turned in a public setting — hotels, the city hall, stores, transit hubs — I was struck by the huge arrays of brochures touting visits to glaciers, ice caves, the Northern Lights, helicopter tours, bar crawls, various museums, etc.

As a city, Reykjavík might be accustomed to heavy foot and vehicular traffic, but what about the areas outside of the capital, such as the waterfalls, the glaciers, the farms, the beaches, etc.?

These are places that are I am sure ecologically sensitive and not ready for the stomp-stomp-stomp of thousands of LL Bean boot-wearing outsiders.

It recalls to mind when I worked in New York’s North Country. The Adirondacks, with its clean air, hiking trails, lakes and other natural attractions, were alluring for visitors.

The High Peaks, particularly Mount Marcy, the highest peak in New York, were in danger of being loved to death, however.

Rare plant species and wildlife habitats were being damaged or endangered by so much foot traffic. Long holiday weekends saw a parade of cars filled with hikers.

The idea of getting away from civilization and enjoying solitude in nature became increasingly harder to achieve with so many people coming.

So it is with Iceland and its tourists. Sure, outsiders are good for the local economy, but ultimately at what price?

Related: