The rampaging wildfires in California that have claimed the lives of at least six people are a reminder of the unpredictability of nature but also the bravery of those on the front lines fighting such blazes.

The so-called Carr Fire — one of several raging in California — consumed nearly 100,000 acres and destroyed more than 700 homes in just a week.

For me, devastation on such a scale is difficult to comprehend.

My first — and thankfully only time – reporting on a wildfire was one that destroyed “only” 300 acres and one house. By way of comparison, the Carr Fire was more than 300 times the size of the one I experienced.

Still, it was memorable.

It was May 16, 1991, and I was in Saranac Lake, N.Y., in the Adirondacks. It was around 3 p.m. and there was suddenly a caravan of fire trucks from neighboring Lake Placid wailing through the downtown.

Oddly, they were not stopping anywhere in the village but were making a beeline out of town.

That there were so many of them, that they were in such a tearing hurry and the route they were taking just made my news senses tingle.

So, I did what I’ve done since I was a kid in the Bronx: I followed the fire trucks.

That led me about 10 miles out of town to a hamlet called Vermontville. It did not take long to see the plumes of smoke.

The fire had leap-frogged ahead of efforts to contain it. More than 300 firefighters from 35 departments were called. The authorities at the time said it was the biggest wildfire in the area in 20 years.

“Water! Where the hell is my water?!” could be heard crackling over radios as firefighters dragged hoses. Later, civilian volunteers brought milk cans filled with water for the soot-covered firefighters working in the 84-degree heat.

What I am about to say next falls under the heading of “Don’t try this at home”: I roamed around alone and unescorted, snapping pictures and taking notes.

At one point I was busy taking a photo and there suddenly was this “Whooooosh!” and burst of heat. While my back was turned, flames had swallowed a tree, quickly reaching its crown.

Talk about great balls of fire.

It was like getting an instant sunburn.

This was a time before cellphones, so I found a home that was being evacuated, interviewed the occupants (one of whom was disabled and being removed by a State Police helicopter) and asked if I could use their landline.

I called my then-wife to tell her where I had gone and to assure her I was fine (I left out the part of the burning tree and that I was calling from an evacuated home) and then quickly called my editor to save me some space in the next day’s paper.

My story and photo were above the fold with the headline “Fire ravages Adirondacks” and a breathless lede: “VERMONTVILLE — A wind-whipped fire ravaged about 300 acres of woodlands here Thursday, destroying one house, forcing families to flee their homes and injuring seven people.”

Now take my limited experience and amplify it by a 10,000 percent and think of those firefighters and smoke jumpers who do this kind of thing for a living.

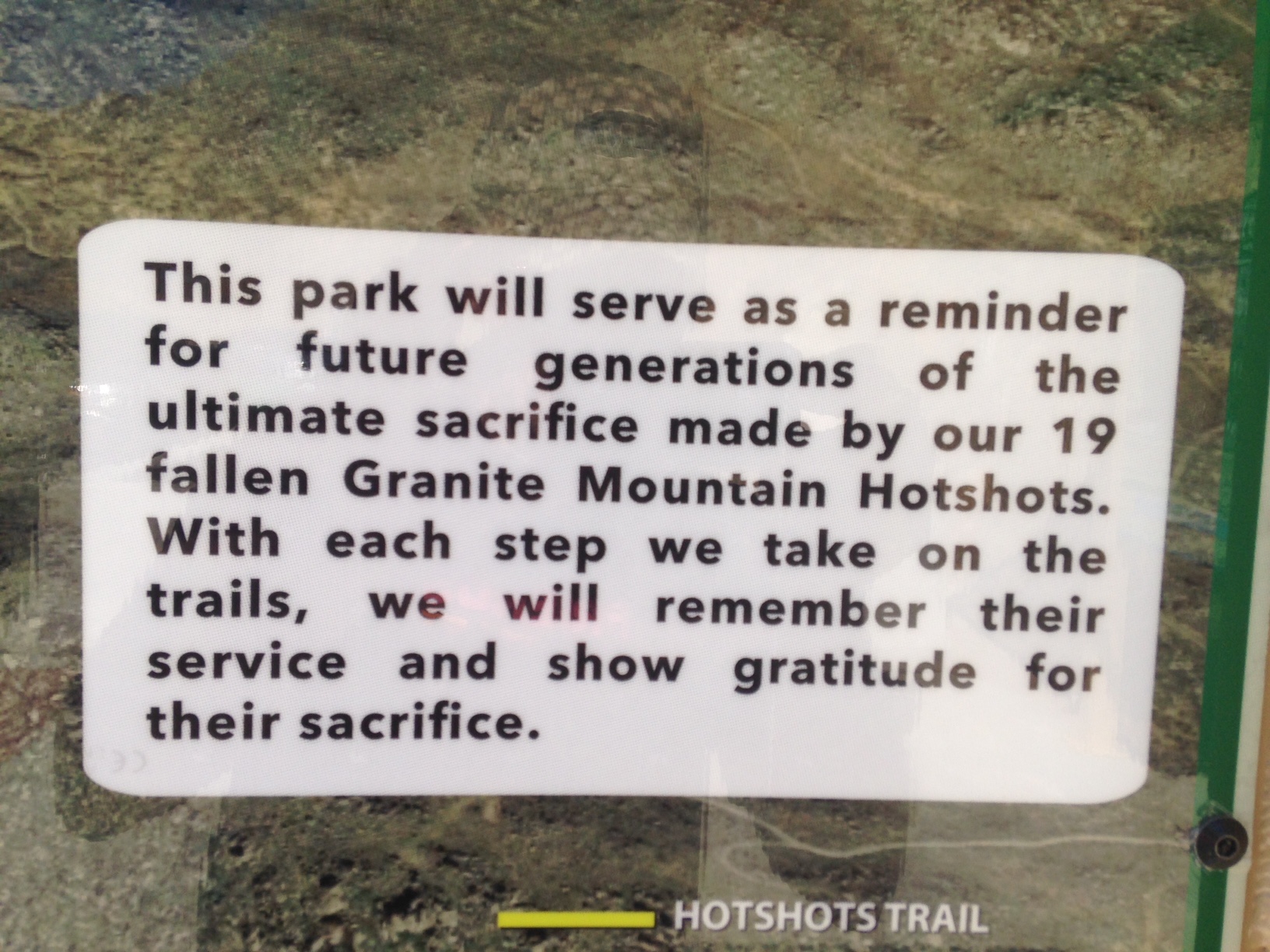

My wife and I visited the Granite Mountain Hotshots Memorial State Park in Arizona where 19 “hot shots” (wildland firefighters) perished fighting a wind-whipped fire outside Yarnell, Az., in 2013.

It was the largest number of firefighters killed in a single incident since the 9/11 attacks.

Whether it’s one firefighter saving a child from a burning building or a team of them trying to saving an entire community, what these people do is awe-inspiring and deserve our respect and gratitude.

Related:

http://aboutmenshow.com/being-a-fire-buff-goes-beyond-trucks-and-sirens/